Tag Archives: End of Life

Social media and the healthcare establishment: a power struggle

You may be already familiar with the controversy that a couple of newspaper articles have generated regarding the tweets of Lisa Adams, a woman who is terminally ill, and who has been openly blogging and tweeting about her journey as a patient diagnosed with an incurable cancer. She is not alone in doing this. Dr Kate Granger is also a young woman diagnosed with a terminal cancer, as well as a doctor. She too has chosen to share her experience online, including very personal feelings and pictures of her ordeal.

One could look at this anecdotes phenomenon from many angles, and indeed most have been covered: ethical, public health, medical, social media, patient engagement… To me, the essence of the debate is a very old one: it all boils down to a power struggle, because

the irruption of the Web 2.0 has fostered a paradigm shift within the healthcare landscape.

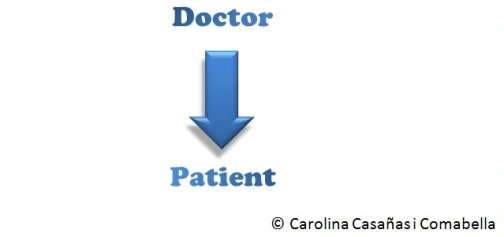

Not many years ago, the healthcare system was dominated by what has been called the biomedical model. In this model, doctors* knew best, and patients did not question what they were told. Patients were passive recipients of the medical knowledge. We could represent this model in a very simple diagram:

More recently though, things have changed. The biomedical model is slowly but steadily being replaced by the biopsychosocial model. There are many differences between this model and the traditional, biomedical model. I will only focus on the different doctor-patient interaction. In this model, patients take a proactive role. Instead of being passive, the patient has become an engaged and empowered stakeholder, thus changing the doctor-patient relationship:

In my opinion, the debate about patients’ tweets is a symptom that shows how the establishment struggles with this new paradigm. I think it’s interesting how so many people are scared of social media, because it gives power to the people. Until now, it was just us (doctors, journalists, politicians, scientists…) who told things the way we thought they were. Our vision of the world was the right one, and “the lay person” listened. But now, with the Web 2.0 (and this includes social media), everyone and anyone can tell things the way they think they are, and our version of the story is no longer the right one. And we are forced to listen.

It is time that the self-appointed experts give some room to the patients, because thanks in part to social media they are going to take the centre stage whether you like it or not. After all, is this not the essence of patient-centred care?

* Just to make this post easier to read, I chose to simplify and use the word “doctor”. Of course I mean the medical establishment, including nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists, physiotherapists and so on. I’m sure you understand what I mean when I say “doctor”.

Twitter and Palliative Care

It is not often that I come across a paper that I find not only interesting, but also useful. And it is even rarer for me to read a scientific paper about social media that tells me something I did not know already. As other fellows geeks will very well know, real news about social media nowadays come almost exclusively from blogs and from Twitter.

So I was very pleased to find Craig Nicholson’s brief paper titled Palliative care on Twitter: who to follow to get started. In it, Nicholson suggests a number of Twitter accounts to follow, if you are interested in palliative care. Not only does he list a few of them (such as @kesleeman AKA Dr Katherine Sleeman, @EAPCOnlus AKA the European Association of Palliative Care or @thewpca AKA Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance, among others), but he also describes the account in a short paragraph: who is it, and what will you get from them.

It is very refreshing to see that despite all the social-media-hating-dinosaurs in the health care world, there is still a minority of e-pioneers getting good publications out there, and this is one of them.

If you are new to Twitter and interested in palliative care, this is the paper you need to read.

Telehealth and eHealth: Ageing well: how can technology help? The RSM Conference 2013

For the last couple of days, I have attended the Annual Conference of the Royal Society of Medicine’s (RSM) “Telehealth and eHealth 2013 Conference: Ageing well: how can technology help?”, organised by the RSM’s Section on Telehealth & eHealth. Personally, it has been a hugely inspiring conference, because it focused on the three key elements of this thing we call eHealth. I firmly believe that the 3 edges of the triangle of eHealth should be patient-centredness, good use of technology and public health:

- This conference has been highly patient-centric. I recently attended the Medicine 2.0’13 Conference and was disappointed of how much it was focusing on the business and data-harvesting aspects of eHealth. This is only my perception, which is probably due to the fact that I have always worked, and am passionate about, the public sector. So it was great to really feel how all these outstanding speakers (Mary Baker, Charles Lowe, Baroness Masham of Ilton, Malcolm Fisk or Rabbi Yehuda Pink, amongst others) do genuinely care about the people, about the patients. I was also pleasantly surprised by the humble and realistic talk about care homes by BUPA Care Services Medical Director Andrew Cannon.

- Needless to say, this conference was very strong on how technology can help older people live healthier lives, by improving their quality of life (QoL). Having worked at the University of Oxford’s PROMs Group for a while, I know well the theoretical and methodological underpinnings of PROMs, so I completely agree that PROMs must be our weapons of choice to measure the impact of eHealth on people’s QoL. Two of my favourite quotes from the last two days are very illustrative of the approach to technology and health care during this conference. During his presentation, Dr M Vernon said that “we can use the technology we already have to improve health care”. I could not agree more: we must keep things as simple and as affordable as possible, if we want eHealth to become really mainstream in health care. My other favourite quote was by Rabbi Y Pink: “technology is God’s gift to humanity to improve our quality of life”. This made an atheist like myself smile, in a good way. It is crucial that relevant people in the community can pass the message in such a clever, easy to understand manner.

- Last, but not least, I did thoroughly enjoy the focus on public health that this event had. In my humble opinion, there is still a lot (a lot) to be done in terms of public health and eHealth. It was great to learn about relevant initiatives from the European Commission, such as the imminent Green Paper on mHealth. I intend to post about this when it is published in a few weeks.

Finally, I was personally very interested to hear about many existing end of life/palliative care and dementia eHealth projects.

This is my take on this year’s RSM Telehealth and eHealth Conference. I would be very interested to hear your views, either via Twitter or as a comment to this post (below).

Would you let me die at home, dear?

The BMJ recently published a Personal View article by William Tosh, an anesthesiologist who shares his experience of looking after his father during his last days of life: Choosing to die at home can be tough on the family. In it, he describes the feelings of guilt that he and his close family felt whilst trying to support the best they could his father’s wishes to die at home. Tosh talks about how he struggled with feelings of guilt and resentment, having his home “invaded” with medical devices and staff. His father received excellent end of life care, however he questions if dying at home was the best option in that particular case. He explains how

feelings of panic […] began to surface: there was now nowhere for the family to escape.

I think Tosh has written a very brave letter, sharing his emotional roller coaster and exposing personal feelings in a sensitive manner. More often that we would like to admit, another physician’s account of experience is much more valued than a lay person’s similar account. In this sense, Tosh’s text is a very powerful one, since it brings to the arena a topic that it is not always easy: when the dying person’s wish to die at home is not completely shared by their relatives.

In the last decade or so, there has been a shift in palliative care, acknowledging that most people prefer to die at home, and hence teams and policy makers have been advocating for it. On the other hand, some literature has highlighted an underlying issue: the dying person’s views may not be the same as their carer’s views. In other words, I may want to die at home, but my family may not be prepared for it. This can bring feelings of personal inadequacy (am I a bad person? Don’t I love my father/mother/husband…?), guilt, isolation (it is not easy to talk about this) and resentment. Tosh’s letter illustrates this very well.

I do realise that I am exposing my own reactions to Tosh’s article, and of course my opinion is biased by my own experience of helping dying people and their relatives in a Mediterranean culture. Nonetheless, I think articles like his are a valuable addition and much needed, because they bring attention to a sensitive topic and encourage us researchers and clinicians to discuss it in the open. There are probably no easy answers: each family is a different world, and each disease is different experience.

What is your view?