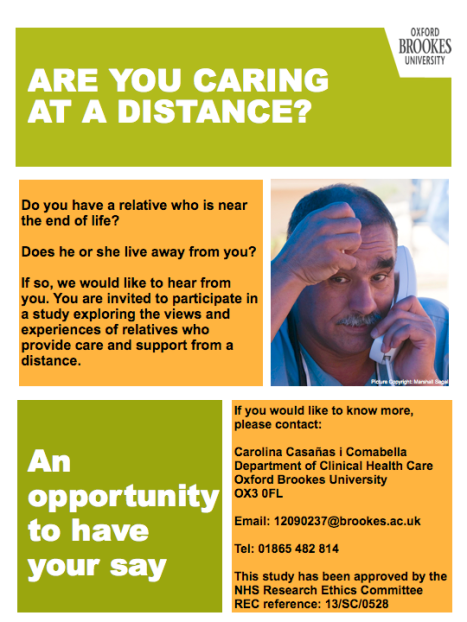

Over the last few days I have attended, and thoroughly enjoyed, the 10th Palliative Care Congress in Harrogate (UK). One of the best sessions that I attended during this conference was the masterclass Supporting sexual intimacy in palliative care, by community clinical nurse specialist in palliative care Dr Bridget Taylor and cancer nurse and psychosexual therapist Dr Isabel White. The following is my take on it.

Adam and Eve, sculpture by Ellen Kolk (1970).

Photo credit: Creative Commons by Tony Bowden

This workshop highlighted the importance of sexuality and intimacy at the end of life, a topic that is often overlooked, because a) most cultures tend to be embarrassed to ask about it, and b) we seem to feel that when one is dying, intimacy is not that important. The session gave a very interesting overlook on the topic, and captured really well the different aspects of sexual intimacy: it is not just about intercourse, but, rather, a range of behaviours and emotions around intimacy, commitment and passion. This is known as the triangular theory of love (Sternberg, 1986).

I was particularly impressed by the respect and tender manner of Taylor & White, who used very powerful case studies to illustrate their arguments. My take-home message after this session was learning the importance of talking about sex. We all know how to talk about it when we have a cold: “I have a sore throat”, “My head hurts”, “I have a blocked nose”, “I feel drowsy”, “I need to sleep in order to feel better”, and so on. But when it comes to sexuality we often do not know how to talk about it, because we are not used to discussing it. It is more often than not a topic that only lives within ourselves. If we never talk about sex, even when things are fine, we will not have learnt a way to talk about it. This, in turn, will probably make it difficult to talk about it when problems arise, and very challenging to find a way to ask our patients about it.

We have to find our own language to talk about sex.

The authors of this workshop have kindly made the slides available through the PCC website.

Further reading:

Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological review, 93(2), 119.

Taylor, B. (2014). Experiences of sexuality and intimacy in terminal illness: A phenomenological study. Palliative medicine.